Thinking Beyond Ideology

A response to new centrist revisionist histories.

(Credit for the voiceover for this article goes to the great Samuel Lipson)

Ever since the 2024 election was called for Donald Trump in the early hours of November 6th, the anti-Trump political world has been engulfed in a very familiar debate. Split along roughly the same lines that divided them during the 2016 Democratic primary, each side of the left-of-center political world has been engaged in a blame game, with the ultimate object of laying the failure of the Biden administration at the feet of their opponents. It has also been difficult for the left side of this debate to take it all that seriously. To many of us, the entire discussion is yet another iteration of a dispute that should have ended with Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016. To see yet another set of centrist politicians wind up hated and thrown out of power is to receive an unneeded reminder of a truth that we have known all along: that Democrats are weak, ineffectual center-rightists who cannot be reformed and must be cast out of power. In this light, it can be hard to find much motivation to engage with a class of perpetually wrong figures once again attempting to claim that everything is our fault as a means of denying their own, very real culpability in disaster.

This stance is understandable, and it may end up working out. In the month since Trump’s inauguration, the bulk of the slowly-returning liberal political energy has coalesced around figures like Bernie Sanders, who has seen massive social media success and sold-out crowds simply by repeating the same messages he has said all along. Kamala Harris’ support in early primary 2028 polling has started to shrink while Democratic voters themselves have registered unprecedented levels of dissatisfaction towards their own party leaders. Attempts by said leaders to reveal silver linings or paint themselves as helpless have been met with such anger and mockery that even centrists have begun to hope for an anti-establishment moderate movement—one that, as of now, has precisely nobody representing it.

All of this is possibly the only encouraging trend in politics today. It is also something that we cannot take for granted. As all of this has occurred, America’s discredited centrists have spent a significant amount of time and effort crafting new narratives of the past few decades of politics that they hope will allow for their stance to survive the disaster of the Biden era. Placing ideology at the center of voter behavior, they have told a new history of 21st century American politics: one in which Obama’s dual victories were triumphs of moderation and that Kamala Harris let Trump by letting herself be seen as too extreme relative to him. It’s entirely self-serving, flatly absurd on numerous levels, and also something that the left has largely refrained from addressing directly. This could be a real mistake. More than just inverting their framework on our own terms—i.e., casting every Democratic success as actually leftist and every failure as centrist—we must strike at the core of their argument: that perceived ideology and ideological shifts are what explain contemporary political history.

What Centrists are Saying About 2024

In the spirit of fairness, this article will begin with what these centrist groups and writers have been saying over the past four months in their own words. As tempting as it might be to simply mock their stances as simple re-runs of the same arguments that proved so wrong in the past, these groups have updated their latest talking points to account for new circumstances, which means that renewed rebuttals are warranted. For a succinct summation of their worldview, a recent memo from Third Way, a corporate-funded centrist think tank, serves quite nicely. Titled “Why Democrats Must Reject the Pledges” and addressed to “Every Democrat Pondering a 2028 Presidential Run,” this piece of writing goes over Third Way’s understanding of the 2024 election and gives advice for candidates in the future. For the former, their verdict is as such:

For 106 days, Kamala Harris ran a campaign targeted to appeal to swing voters and the moderates who make up a sizable chunk of a winning Democratic presidential coalition. But there were no number of American flags at the DNC, Never-Trump Republican endorsements, or visits to the border that could overcome the weight of the politically fraught positions she took to satisfy the far left in the 2019 primary. Whether it was banning fracking, opening the border, or providing federally-funded gender-reassignment surgeries to undocumented immigrants, Trump and his allies hung these anvils around the neck of the Vice President and persuaded voters that she was “dangerously liberal.” Facing a choice between a candidate they believed was extreme on policy or one who was extreme in his behavior, the American people decided they’d rather take their chances with the latter.

I think this is a very useful paragraph, mostly because it actually engages with an important fact about the 2024 campaign that many centrist writers and groups choose to ignore: that Kamala Harris’ actual campaign for president fit their preferences almost perfectly. And Third Way’s response to this, as shown above, is a simple one: that all of these endeavors were good, wholly productive, and only failed to secure the election because the legacy of the progressive campaign that Harris ran in 2019 was too much to overcome. In their story, the villains responsible for Trump’s rise are the “far-left groups” that pushed her to take her old positions in the first place, and the path to success for Democrats entails future candidates completely ignoring such organizations. One tempting possible response to this might be to say that Harris’ primary effort in 2019 represented an extreme iteration of fealty to these groups even by the standards of the left: that she went far beyond the likes of Bernie Sanders in centering lame activist causes, and that a failure as a result of that doesn’t necessarily mean that any candidacy to the left of Bill Clinton is dead on arrival. All else equal, wouldn’t it be best to just cut bait, disavow a clearly defective candidacy none of us supported, and argue that a “real” progressive candidacy wouldn’t taint itself in the ways that she did to herself?

Perhaps. However, such a point notably concedes the core of Third Way’s argument: that Harris primarily lost in 2024 because she was seen as too extreme relative to her opponent, and that past Democrats succeeded because they avoided such pitfalls. If one looks at the actual data from the election, they will find that the story here is not nearly as straightforward as Third Way makes it out to be. For just one example, it’s helpful to look at a data point that centrists often cite: a post-convention, pre-debate September poll from the New York Times that found more voters viewing Harris as too liberal than Trump as too conservative. While this is true, it is also the case that a majority of respondents to their survey saw Harris as either “not too far either way” or “not liberal enough,” and that other, differently-phrased surveys found dramatically different results about Trump’s perceived extremism. Case in point: when Gallup asked about how voters felt about each candidate’s views in their poll on candidate attributes two weeks later, they found statistically identical shares of respondents declaring each candidate too far in each direction.

One particularly notable thing about this Gallup poll is that it directly contradicts the most important part of Third Way’s argument as to why progressives should be completely shut out: that all of her valiant efforts to move to the center were made completely futile by the sheer toxicity of her past left-wing positions. Judged relative to results by prior polls both conducted by Gallup, the results here strongly indicate Harris actually did succeed in her high-profile effort to cast herself as a moderate and Trump as an extremist. Compared to Gallup’s June poll of candidate attributes between Trump and Biden, perceptions that Trump was too conservative increased by 4% while perceptions that the Democratic candidate was too liberal went down by 5%. A later poll from Gallup showed even more success by the Harris campaign on this front. Conducted in October, this survey asked voters about how concerned they were about each candidate being “aligned with people who hold radical political views,” and it showed meaningfully more respondents saying they were either very or somewhat concerned with Trump’s ties than Harris’. As shown below, the then-former President saw 55% of voters declared themselves worried about his connections, while the then-Vice President saw a comparatively smaller 49% say so about hers.

When all was said and done, it was Trump, not Harris, who saw the most concern from voters about his connections to the precise kinds of partisan groups that Third Way and others are currently vilifying. And as far as the Harris campaign is concerned, this was a real success! As a result of their advertising in rhetoric, they managed to make Americans more concerned about Trump’s radical connections than Harris’ in spite of the fact that she truly did embrace the fringe during her 2020 campaign. It’s also safe to say that nobody knows this more than the Third Way wing, which spent a great deal of time before the election preparing to cast this legitimately successful effort as the reason why she won. But since the campaign’s real success in moving Harris to the center and Trump to the right didn’t end up bringing in many real voters, they have now chosen to pretend that the entire effort had no impact, all for reasons outside of their control.

In actuality, these efforts did have impacts. But this success didn’t end up winning over many voters, which renders the project a retrospective waste in the sense that it kept the campaign from addressing its more important liabilities. For all the time they spent advertising Kamala the Cop, the Harris campaign and its allies wasted valuable resources that it could have spent on separating her from Biden, providing voters a sense of what she stood for, or making her look like a leader. As a result, Trump, the more experienced candidate, wound up being seen as stronger and more decisive.

From there, the results speak for themselves. Contrary to Third Way’s description of his win as a case of voters choosing a candidate who was extreme in his behavior over one who was extreme on policy, the 2024 election would be more accurately described as the opposite, wherein voters chose a candidate they viewed as a riskier choice with more concerning connections to extreme groups because they thought his personal characteristics made him best suited for the moment.

What Centrists Are Saying About History

Even in light of all of this, context is still very important. While Harris may have wound up bringing the question of extremism and extreme connections to a draw by the end of the campaign, ideological perceptions could still be said to be the cause of her loss if she was seen as exceptionally more extreme relative to past Democratic candidates. Centrists have argued exactly this, creating something of their own revisionist history of the past 25 years of politics in the process. This history, as one might expect, argues that all of the Democratic successes of the century were a result of the party moving to the center and that all of its failures stem from foolhardy swings to the left. It focuses primarily on Barack Obama, who they have painted as a politician whose great genius was just saying popular things. By spurning activists and making tough compromises, they say, he was able to effectively position himself in the middle and bring the party to its highest levels of support since the New Deal era as a result.

The problem for them is that this revisionist history is not true whatsoever. Unlike Harris’ perceived ideology, which actually is a somewhat complex case of differing perceptions that changed over time, the story of Obama’s perceived ideology is remarkably simple. During both his outsider run in 2008 and his re-election bid in 2012, voters saw Obama as more liberal than them and more radical than his opponents.

Full stop.

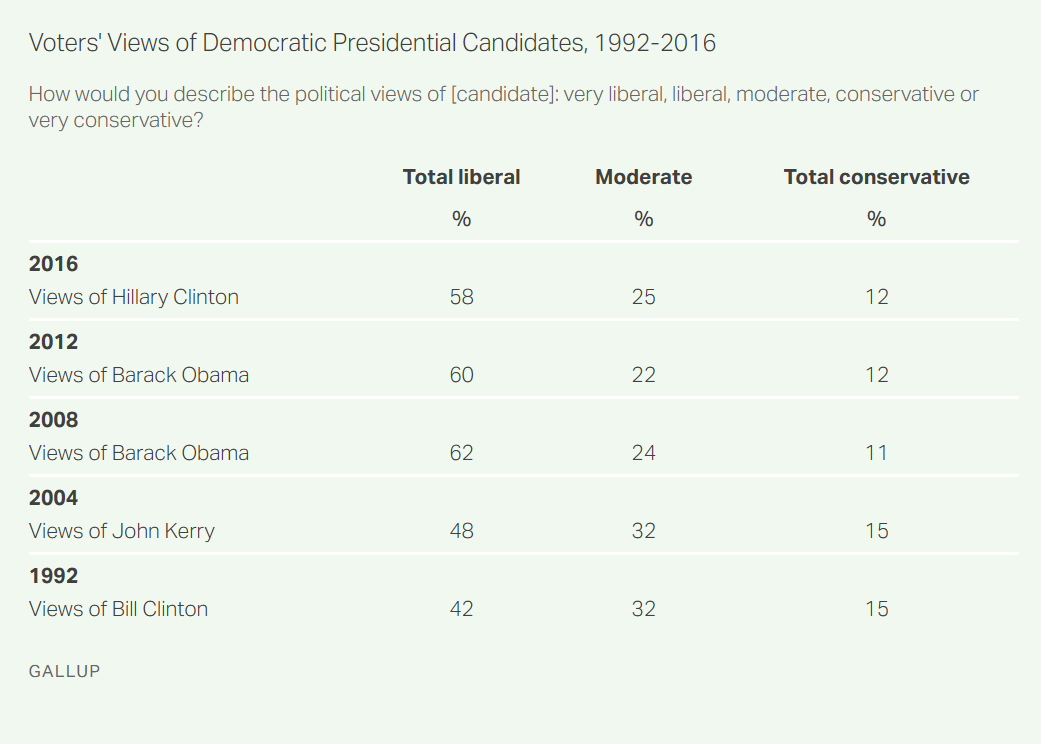

Consider, for instance, Gallup’s poll of perceived candidate ideology, which showed Harris and Trump effectively tied in terms of perceptions of their extremism. Gallup also held the same poll with both candidates included in 2004, 2008, and 2012, providing us with a sample size of both of Obama’s elections and the Democratic loss that preceded it. For 2004, it is true that the Democratic candidate was seen as more ideological than his Republican counterpart. Back then, 47% of voters saw Kerry as too liberal, while only 40% of voters saw Bush as too conservative, and the Democrats lost. But, and contrary to what centrist history says, this gap didn’t change when Democrats won four years later. In fact, when Obama was on the ballot for Democrats, he actually saw his party’s relative standing on this question get worse. In 2008, 45% of voters saw him as too liberal, a full ten points more than the 35% of voters who saw John McCain as too conservative. If it were actually the case that elections are decided primarily along ideological lines, he would have been the worst-performing Democratic candidate of the 21st century.

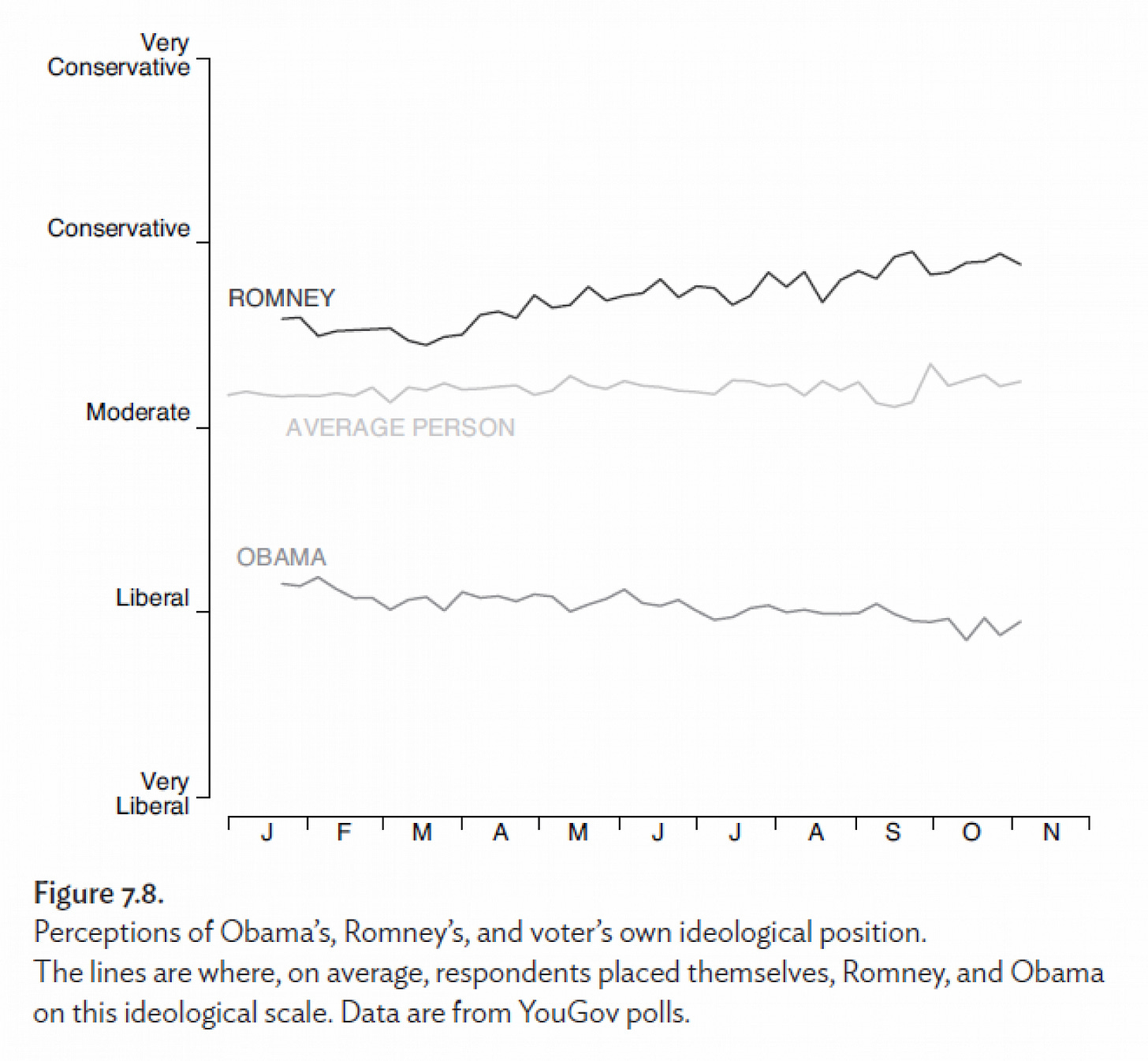

One may call this win that year a Great Recession-induced fluke if they wish, but that explanation would fail to account for Obama winning again in 2012, when an increased 47% of voters judged him to be too liberal while a smaller 43% called Mitt Romney too conservative. As the graph below shows, voters saw Romney as both closer to the center and closer to their own views than Obama throughout the 2012 campaign.

(Fun fact about this graph: I actually found it from an old Matt Yglesias article from the 2016 primary where he argued that Bernie Sanders’ attacks on Clinton’s moderation were likely to help her in the general election by making her look more centrist to voters. He used the above graph as proof that voters “would like a more moderate Democrat” in spite of the fact that Obama won the election in question and Mitt Romney did not. This may seem completely inexplicable to those of us reading it now, so keep in mind that it was published during a period when it seemed overwhelmingly likely that Clinton would win by an even larger margin than Obama did in 2012. When this appeared to be in the cards, Yglesias had no issue with describing Obama’s victory for what it was: a triumph by someone who was seen as more ideologically radical than their opponent. But now that Obama’s victories are seen as high-water marks for Democrats, he has framed his wins as the exact opposite.)

Still, what about Obama and the Groups? This might be a place for wiggle room for the likes of Third Way. After all, even if Americans saw Obama in 2008 and 2012 as more ideological relative to his opponents than Harris in 2024, perhaps those concerns were simply less salient with him than they were with her because radicals received less attention during the 2008 campaign. Once again, this was not the case at all. In fact, Gallup only first started asking voters this question about radical groups in the first place in response to the controversies surrounding Obama’s relationships with Bill Ayers and Jeremiah Wright in 2008. The result that year was a 52% majority of voters saying that they were either very or somewhat concerned about Obama’s connections while only 42% said so about McCain. Across the three times that Gallup has surveyed this question, Obama 2008 marks the sole instance where voters have been more worried about the Democrat’s radical connections than the Republican. As shown below, both a Joe Biden during the height of BLM and a Kamala Harris being constantly slammed as for they/them did better relative to their opponents in this metric than Obama did during the year he won in a landslide.

In addition to this, and further contrary to centrist history, Obama was also seen as the most liberal of any Democratic candidates across all of Gallup’s polls from 1992 to 2016. 60% supermajorities regarded him as such in both 2008 and 2012.

Search for a Barack Obama whose principal strength in either of his elections was his perceived moderation and you’ll be hard-pressed to find one. Although hardly any of the predictions made following his successes have wound up bearing water over the past 13 years, it still is true that his dual wins represent proof of concept for winning nationally without necessarily winning the center. The portrait of him as a proto-popularist Bill Clinton redux is simply an incorrect one, and the things that allowed him to succeed came from someplace else.

Concluding Thoughts

So, what can we make of all of this? First, none of this is proof that ideology, and ideological perceptions, doesn’t matter in U.S. elections. They obviously do, and like all things, it's generally better to be closer to where voters are than far away from them. Those of us with more radical beliefs will do well to remember this, especially in light of the struggles that Bernie’s ideological successors have seen in their attempts to match the heights that he saw during his presidential runs. But even with that said, it’s important not to fall for the pseudo-history that America’s centrists have spent the last few years crafting: that the story of the Trump era is a tidy narrative of liberals and leftists unlearning the common-sense lessons of the Obama era, moving too far from the center, and leaving Middle America in the arms of an authoritarian lunatic.

This is a comforting theory, at least insofar that it provides a simple solution that many of its proponents agree with on the merits. The problem is that it’s just not true. Although one might be able to easily construct a series of anecdotes that make 2008’s Barack Obama look like a radical centrist and cast Kamala Harris as the next coming of Bernardine Dohrn, that’s just not how the public saw it, and it wasn’t the basis of how they voted. At the end of the day, Obama won in a landslide at the same time that voters saw him as more extreme than his opponent, while Harris was swept in every swing state despite more effectively leveraging her opponent’s radical connections. However important ideology may be, voters simply cared more about different, character-based traits, many of which were buttressed by the exact things that also made Obama look more radical.

As for what these traits are, I will finish this piece with a note on the legacy of the other Democratic president that centrists often point towards as proof of concept for their ideas: Bill Clinton. Unlike Obama, Clinton is a clear-cut case of a Democratic politician actively working to move themselves towards the center, succeeding, and then winning. Gallup polling showed only small minorities of voters (33% in 1992 and 36% in 1996) describing him as “too liberal” during both of his elections. At the same time, however, it is also true that Clinton ended his presidency with most Americans sick of his triangulating act and desperate for more decisive leadership. To that end, they preferred Texas Governor George W. Bush over Al Gore by landslide margins for most of the 2000 campaign, largely for the reason that he was seen as a strong leader who could turn the page on years of rudderless sleaze. From this, Gore was forced to break from Clinton on everything from the Lewinsky scandal to economics in order to come back and narrowly win his race.

If ideology and built-in advantages were all that mattered, Gore would have never had to spend a moment doing any of this. But it wasn’t, and it still isn’t. Voters care about things beyond how much you can pander to them, and they do so for largely logical reasons. If Democrats choose to follow Third Way’s advice and ignore this truth in favor of the easy path of shutting out groups with names like “GreenLatinx,” they may find themselves in the wilderness for longer than they need to be.

Excellent post. More or less correlates to what I’ve been thinking. It’s not that isn’t innately harder for ideologues to win elections, it’s the myopic centering of ideology as the sole and uncomplicated means with which voters make decisions.

However toxic certain progressive stances may be and however much influence Kamala’s perceived support for those positions may have hurt her chances, to chiefly blame ideology is to accept the pretense that Trump exists closer to the center ground of American politics. Even if you want to assume we’re an intractably center-right country, Trump and the activists that inhabit the GOP have a preponderance of incredibly unpopular positions on abortion, the environment, healthcare, the welfare state, etc, that they spew vocally and without constraint.

I think we’re all dissatisfied with the Dems current cocktail of ideology but trying to move forward needs to come with a stronger recognition that the political craftsmanship: Messaging, organizing, branding and candidate quality must come first. (this is for us leftists too) The Dems don’t fail *primarily* because they’re too progressive or too centrist but because they’re a staggeringly incompetent and ineffective political organization with no coherent vision or ideological project, no capacity to effectively talk to voters, and comatose, robotic drones as party leaders.

I love your work and I usually do not respond to things I read but your journalism holds a special place for me so I hope to share my thoughts here on that ending ‘Latinx’ reference.

The Hispanic community do not care for, do not know, and resent the term and those very same liberals that use it nonstop. (https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2024/09/12/how-well-known-is-latinx-among-u-s-hispanics-and-who-uses-it/) (One of many articles, just google it for five minutes) (Here's another specifically about the resentment aspect! https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/many-latinos-say-latinx-offends-or-bothers-them-here-s-ncna1285916)

As a Latino who worked in DEI, it was one of the most frustrating things especially given that the X's origins is not all encompassing for this diverse community but is specifically inspired from the Nahuatl language, making it incredibly uninclusive for the minority of Hispanics that are not Mexican in the United States.

On top of this, the X just sounds awful in Spanish if pronounced correctly Latin-'equis', and if not just forces an Anglo pronunciation to fix a problem in English for Spanish speakers that don't even know what it's about to feel included.

The people who always deploy it have been people who want to be viewed as socially progressive but have no further material analysis to understand where it comes from, how it feels and sounds to the community and just are dismissive to what they think in general!

Not that it is not a problem in terms of gender inclusivity, there are just so many other terms that just make more sense. In South America in particular there are lots of people in Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, etc using the term 'latines' with e serving as a general more universal gender ending. We could just use the term 'Latins' or AT WORSE JUST SAY 'LATIN AMERICANS' and that would probably solve things, though I am not a linguist and this is my own speculation.

The point is though, Latinos are not there with the term, are underrepresented in the places where it is being used (mostly university spaces), are, have, and will react badly to a term that feels like a particulary frustrating Anglicismo about gender identity and in this last point, works against protecting the lgbtq community through this inherently negative framing and bad politics.

(Not to make some point that this is why Democrats lost, but it is one of those things that has to be noted, latinos demographically in the United States are one of the strongest groups that want more government to help in their lives while typically holding somewhat social conservative views!)